In my previous blog, I discussed how pension funds have the potential to make the world a better place through their investments. Since then, ABP announced €30 billion in impact investments, and the five largest Dutch pension funds wrote a letter to the informateurs expressing their intent to invest billions in the energy transition. Naturally, there were various knee-jerk reactions. Some feared that pension funds would recklessly burn their participants’ money—an unfounded accusation.

Pension funds have thoroughly informed themselves for years about shifting their investment focus toward better societal outcomes. They never lose sight of risk and return. The question of consequences for risk and return is continually asked. In fact, they are building a stronger foundation for long-term results across the board.

The blinders are coming off. However, challenges remain, as I mentioned in my previous blog. The crucial question is how pension funds intend to achieve their broader goals. Broadly speaking, there are two routes that pension funds can take.

Approach 1: Shifting capital from negative to positive externalities

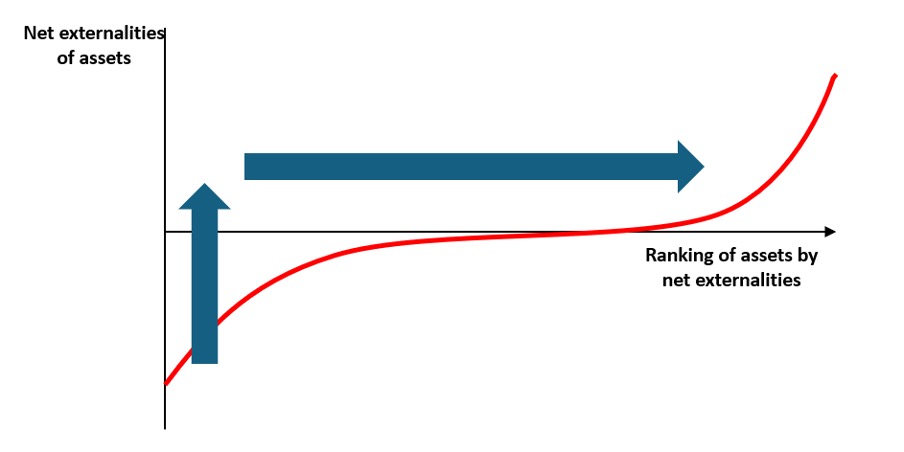

Firstly, they can reallocate investments from assets with negative externalities to those with positive externalities (illustrated by the horizontal arrow in the figure below). Externalities refer to the costs and benefits generated by activities for society, without directly affecting the actors involved (at least not yet). Consider pollution (a negative externality) and knowledge (a positive externality): companies generate them but are not fully taxed or rewarded for them.

This shift (horizontal arrow to the right) can occur within an asset class (e.g., from publicly traded airlines to publicly traded enzyme manufacturers) or involve a move from one asset class to another. Often, it means transitioning from public to private investments. For instance, selling shares in publicly traded oil companies and buying shares in private companies producing renewable energy or lab-grown meat.

Such investment reallocation is relatively straightforward. The main counterargument is that its impact on the real world may be limited: the sold assets end up in the hands of other owners who might manage them poorly. Moreover, research suggests that “brown” companies become even more short-term-oriented through such divestment and may become even “browner.”

However, selling brown assets is only one side of the coin. The other side is where the money is reinvested, which can be green. Increasing investments in green assets does make a difference. Nevertheless, the second route is equally essential.

Approach 2: Enhancing existing assets

The second approach involves improving the externalities associated with existing assets (illustrated by the vertical arrow in the figure above). Much of the economy generates significant negative externalities. To achieve an economy within planetary boundaries, certain activities must shrink or even cease (such as coal-fired power plants). Additionally, many other activities need to become more environmentally friendly—think of transportation, chemistry, food production, clothing manufacturing, housing construction, and more.

Greening existing assets is more challenging than merely shifting assets between portfolios, but it is equally crucial. In some cases, it may seem nearly impossible—try influencing a publicly traded and reluctant oil company’s course of action with limited authority.

However, there are varying degrees of impact. Focused engagement within concentrated portfolios can yield results for many companies. Moreover, when dealing with smaller assets and greater influence, achieving positive outcomes becomes more likely. Consider Swiss pension funds that are making their local housing stock more sustainable—an effort that directly benefits their own participants.

Combining both approaches

Ideally, pension funds should pursue both directions. The previously mentioned proposal for pension funds to invest billions in the energy network aligns well with this approach. There are numerous opportunities for Dutch pension funds. The “quick wins” primarily involve shifting from public to private assets (while avoiding the pitfalls of extractive models) and transitioning from global to local investments—something ABP is doing with its announcement to invest €10 billion in local impact.

However, this poses a challenge for most pension funds, which are traditionally structured for managing passive portfolios. It requires different skill sets to shift capital (route 1) and especially to green existing assets (route 2). External assistance, such as that from dealmakers like InvestNL, is welcome.

Yet, this isn’t uncharted territory. In other advanced pension countries like Australia, Canada, and Sweden, it’s commonplace for pension funds to invest significant percentages in private assets and their home markets. So, what’s stopping us from doing the same?

This blog is the second in a series on pension investments. You can also read Blog 1, Blog 3 and Blog 4.

My other series focuses on CFOs and value creation within enterprises. Feedback is welcome: w.schramade@nyenrode.nl.